Indian Prime Minister Modi addressing the crew of INS Arihant in November 2019. Photo by Prime Minister's Office, Government of India.

Editor’s note: The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project with the Federation of American Scientists, and Matt Korda, a research associate with the project. The Nuclear Notebook column has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. To download a free PDF of this article, click here. To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns, click here.

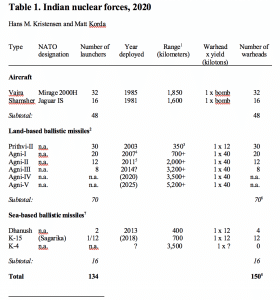

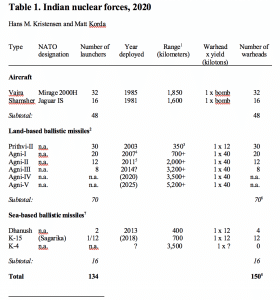

India continues to modernize its nuclear weapons arsenal and operationalize its nascent triad. We estimate that India currently operates eight nuclear-capable systems: two aircraft, four land-based ballistic missiles, and two sea-based ballistic missiles. At least three more systems are in development, of which several are nearing completion and will soon be combat-ready. Beijing is now in range of Indian ballistic missiles. India is estimated to have produced approximately 600 kilograms of weapon-grade plutonium (International Panel on Fissile Materials 2018), sufficient for 150–200 nuclear warheads; however, not all the material has been converted into nuclear warheads. Based on available information about its nuclear-capable delivery force structure and strategy, we estimate that India has produced 150 nuclear warheads (see Table 1). It will need more warheads to arm the new missiles that it is currently developing. In addition to the operational Dhruva plutonium production reactor at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre complex near Mumbai, India has plans to build at least one more plutonium production reactor. Adding to the estimated 5,400 kilograms of reactor-grade plutonium included in India’s strategic stockpile (International Panel on Fissile Materials 2018), the unsafeguarded 500-megawatt Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor under construction at the Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research near Kalpakkam could potentially increase India’s plutonium production capacity significantly in the near future if it achieves criticality as planned in 2020, after a series of delays (World Nuclear News 2019). The director of the research center has additionally stated that six more fast breeder reactors will come online within the next 15 years. Construction of the first two, to be located on-site at the center, would reportedly begin in 2021 and be ready for commercial power production by the early 2030s (Kumar 2018).

KristensenKorda_India Nuclear Notebook Table1_TandF Nuclear doctrine Tensions between India and Pakistan constitute one of the most concerning nuclear hotspots on the planet. These two nuclear-armed countries engaged in open hostilities as recently as February 2019, when Indian fighters dropped bombs near the Pakistani town of Balakot in response to a suicide bombing conducted by a Pakistan-based militant group. In retaliation, Pakistani aircraft shot down and captured an Indian pilot before returning him a week later. The skirmish escalated into the nuclear realm when it triggered a convening of Pakistan’s National Command Authority, the body that oversees Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. Speaking to the media at the time, a senior Pakistani official noted, “I hope you know what the NCA means and what it constitutes. I said that we will surprise you. Wait for that surprise.… You have chosen a path of war without knowing the consequence for the peace and security of the region” (Abbasi 2019). While India’s primary deterrence relationship is with Pakistan, its nuclear modernization indicates that it is putting increased emphasis on its future strategic relationship with China. All the new Agni missiles have ranges that indicate their primary target is China. This posture is likely to be reinforced after the 2017 Doklam standoff, during which Chinese and Indian troops were placed on high alert over a dispute near the Bhutanese border. Tension remained high in 2019, with troop injuries on both sides of the border (BBC 2020). The expansion of India’s nuclear posture to take a conventionally and nuclear superior China into account will result in significantly new capabilities being deployed over the next decade, which could potentially also influence how India views the role of its nuclear weapons against Pakistan. According to one scholar, “we may be witnessing what I call a ‘decoupling’ of Indian nuclear strategy between China and Pakistan. The force requirements India needs in order to credibly threaten assured retaliation against China may allow it to pursue more aggressive strategies—such as escalation dominance or a ‘splendid first strike’—against Pakistan” (Narang 2017). India has long adhered to a nuclear no-first-use policy, even though the policy was weakened by India’s 2003 declaration that it could potentially use nuclear weapons in response to chemical or biological attacks (which would therefore constitute nuclear first use, even if it were in retaliation). Yet amid the 2016 dispute with Pakistan, then–Indian defense minister Manohar Parrikar indicated that India should not “bind” itself to that policy (Som 2016). Although the Indian government later explained that the minister’s remarks represented his personal opinion, the debate highlighted the conditions under which India would consider using nuclear weapons. Current defense minister Rajnath Singh has also publicly questioned India’s future commitment to its no-first-use policy, tweeting in August 2019 that “India has strictly adhered to this doctrine. What happens in the future depends on the circumstances” (Singh 2019). Recent scholarship has further called India’s commitment to its no-first-use policy into question, with some analysts asserting that “India’s NFU policy is neither a stable nor a reliable predictor of how the Indian military and political leadership might actually use nuclear weapons” (Sundaram and Ramana 2018). Additionally, although India has long been thought to store its nuclear warheads separate from deployed launchers, there is increased speculation that India may have increased the readiness of its arsenal significantly over the past decade by “pre-mating” warheads with missiles in canisters for a subsection of the ballistic missile launchers, and possibly also storing some bombs at air bases (Clary and Narang 2018, 36–37; Narang 2013). There is still some uncertainty about how ready those missiles are on a day-to-day basis, since only the Agni-V, which is not yet deployed, is reported to be carried in a canister. But this trend will likely strengthen with India’s development of a sea-based leg of its nuclear triad, which, at least in the way the United States and Russia operate ballistic missile submarines, has typically involved mating warheads with missiles. Aircraft Fighter-bombers were India’s first and only nuclear strike force until 2003, when the Prithvi-II nuclear-capable ballistic missile was fielded. Despite considerable progress since then in building a diverse arsenal of land- and sea-based ballistic missiles, bombers continue to serve a prominent role as a flexible strike force in India’s nuclear posture. We estimate that three or four squadrons of Mirage 2000H and Jaguar IS aircraft at three bases are assigned nuclear strike missions against Pakistan and China. The Mirage 2000H Vajra (“divine thunder”) fighter-bombers are deployed with the 1st, 7th, and possibly the 9th squadrons of the 40th Wing at Maharajpur (Gwalior) Air Force Station in northern Madhya Pradesh. We estimate that one or two of these squadrons has a secondary nuclear mission. Indian Mirage aircraft also occasionally operate from the Nal (Bikaner) Air Force Station in western Rajasthan, and other bases might potentially function as nuclear dispersal bases as well. The Indian Mirage 2000H was originally supplied by France, which used its domestic version (Mirage 2000N) in a nuclear strike role for 30 years, until its retirement in the summer of 2018. The Indian Mirage 2000H is undergoing upgrades to extend its service life and enhance its capabilities; the modernized version is called Mirage 2000I. The Indian Air Force also operates four squadrons of Jaguar IS/IB Shamsher (“sword of justice”) aircraft at three bases (a fifth squadron flies the naval IM version). These include the 5th and 14th squadrons of the 7th Wing at Ambala Air Force Station in northwestern Haryana, the 16th and 27th squadrons of the 17th Wing at Gorakhpur Air Force Station in northeastern Uttar Pradesh, and the 6th and 224th squadrons of the 33rd Wing at Jamnagar Air Force Station in southwestern Gujarat. We estimate that one or two of the squadrons at Ambala and Gorakhpur (one at each base) are assigned a secondary nuclear strike mission. Jaguar aircraft also occasionally operate from the Nal (Bikaner) Air Force Station in western Rajasthan. The Jaguar, designed jointly by France and Britain, was nuclear-capable when deployed by those countries. The so-called DARIN-III precision-attack and avionics upgrade of half of India’s Jaguar fleet achieved initial operational capability in November 2016, and air force operations were approved in December 2016 (Ministry of Defence 2017). This avionics upgrade, which is expected to be completed on the second half of the fleet by 2024, was originally intended to be coupled with a long-planned engine upgrade; however, this proposal was scrapped in August 2019 due to its prohibitive cost and long timeline. Instead, the air force will phase out its Jaguar fleet over the next 15 years. In October 2019, India’s Air Chief Marshal declared that six Jaguar squadrons of approximately 108 fighters will begin retiring in early 2020 (Shukla 2019a). India is searching for a modern fighter-bomber that will probably take over the air-based nuclear strike role in the future. On September 23, 2016, India and France signed an agreement for delivery of 36 Rafale aircraft (Ministry of Defence 2017). The order was considerably reduced from initial plans to buy 126 Rafales. The Rafale is used for the nuclear mission in the French Air Force, and India could potentially convert it to serve a similar role in the Indian Air Force. The Indian Defence Minister formally received the first Rafale (RB-001) at a special ceremony in France in October 2019, followed by two more a month later. Initially, the first four Rafales were scheduled to be delivered to India in flyaway condition in May 2020, with 18 Rafales in total scheduled to be delivered by February 2021, and the whole shipment of 36 aircraft completed by April 2022 (The Hindu 2019a). However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and corresponding lockdowns in both France and India, it is expected that delivery of the first batch of Rafales will be delayed at least three months, as the French training program for Indian Air Force pilots and engineers has been suspended (Peri 2020a). All 36 Rafales will be outfitted with 13 “India-Specific Enhancements,” which include new radars, cold-weather engine start-up devices, 10-hour flight data recorders, helmet-mounted display sights, and electronic warfare and friend-or-foe identification systems. These enhancements are scheduled to be “plugged into” the 36 Rafales after their arrival in India (Dominguez 2019). The Rafales will be deployed in two equally-sized squadrons of 18 fighters and four dual-seat trainers: one squadron (17th “Golden Arrows” Squadron) at Ambala Air Base Station, located only 220 kilometers from the Pakistani border, and the other squadron (101st “Falcons” Squadron) at Hasimara Air Force Station in West Bengal. New infrastructure developments to accommodate the planes are being constructed at both bases, and the Indian Air Force is reinstating both squadrons to active duty after they had both been decommissioned years previously (Shukla 2019b). Land-based ballistic missiles India has four types of land-based, nuclear-capable ballistic missiles that appear to be operational: the short-range Prithvi-II and Agni-I, the medium-range Agni-II, and the intermediate-range Agni-III. At least two other longer-range Agni missiles are in development and nearing completion: the Agni-IV and Agni-V. It remains to be seen how many of these missile types India plans to keep in its arsenal. Some may serve as technology development programs toward longer-range missiles. Although the Indian government has made no statements about the future size or composition of its land-based missile force, short-range and redundant missile types could potentially be discontinued, with only medium- and long-range missiles deployed in the future to provide a mix of strike options against Pakistan and China. Otherwise, the government appears to be planning to field a diverse missile force that will be expensive to maintain and operate.

To prevent global catastrophe, governments must first admit there’s a problemThe Prithvi-II missile was “the first missile to be developed” under India’s Integrated Guided Missile Development Program for “India’s nuclear deterrence,” according to the government (Press Information Bureau 2013). The missile can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead to a range of 350 kilometers (217 miles). Given the relatively small size of the Prithvi missile (nine meters long and one meter in diameter), the launcher is difficult to spot in satellite images and therefore little is known about its deployment locations. It is thought India has four Prithvi missile groups (222, 333, 444, and 555) with about 30 launchers deployed close to the border with Pakistan. Possible locations include Jalandhar in Punjab, as well as Banar, Bikaner, and Jodhpur in Rajasthan. The Strategic Forces Command conducted four user trials of the Prithvi-II in 2019, two of which were night launches carried out in the same event (Sharma 2019). The two-stage, solid-fuel, road-mobile Agni-I missile became operational in 2007, three years after its induction into the armed forces. The short-range missile is capable of delivering a nuclear or conventional warhead to a distance of approximately 700 kilometers (435 miles). The mission of Agni-I is thought to be focused on targeting Pakistan; we estimate that up to 20 launchers are deployed in western India, possibly including the 334th Missile Group. The two most recent user trials were conducted February and October 2018. The two-stage, solid-fuel, rail-mobile Agni-II, an improvement on the Agni-I, can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead more than 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles). The missile possibly began induction into the armed forces in 2008, but technical issues delayed operational capability until 2011. Around 10 launchers are thought to be deployed in northern India, possibly including the 335th Missile Group. Targeting is probably focused on western, central, and southern China. There was one user-trial conducted in November 2018, the first successful night launch. This could indicate that previous technical issues with the Agni-II have since been resolved (The Hindu 2019b). The Agni-III—a two-stage, solid-fuel, rail-mobile, intermediate-range ballistic missile—is capable of delivering a nuclear warhead to 3,200-plus kilometers (1,988-plus miles). The Indian Ministry of Defence declared in 2014 that the Agni-III is “in the arsenal of the armed forces,” (Ministry of Defense 2014) and the Strategic Forces Command conducted its fifth user trial on November 30, 2019 from Abdul Kalam Island on India’s east coast. The missile failed this first night trial, deemed a “very crucial” test, with the missile falling into the sea after first stage separation (Rout 2019). It is still early in the Agni-III deployment; there are probably fewer than 10 launchers deployed, and the full operational status is uncertain. The additional range potentially allows India to deploy the Agni-III units further back from the Pakistani and Chinese borders. More than a decade ago, while the missile was still under development, an army spokesperson remarked, “With this missile, India can even strike Shanghai” (India Today 2008), but this would require launching the Agni-III from the very northeastern corner of India. From that region, the Agni-III would for the first time bring Beijing within range of Indian nuclear weapons. India is also developing the Agni-IV missile, a two-stage, solid-fuel, road- and rail-mobile intermediate-range ballistic missile with the capability to deliver a single nuclear warhead up to 3,500-plus kilometers (2,175-plus miles); the Ministry of Defence has listed the range as 4,000 kilometers (2,485 miles) (Ministry of Defence 2014). Following the final development test in 2014, the ministry declared that Agni-IV “serial production will begin shortly.” Since then, three user launches have been conducted by the Strategic Forces Command, the most recent in December 2018, but the missile is not yet fully operational. Although the Agni-IV will be capable of striking targets in nearly all of China from northeastern India (including Beijing and Shanghai), India is also developing the longer-range Agni-V, a three-stage, solid-fuel, road-mobile, near-intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of delivering a warhead more than 5,000 kilometers (3,100-plus miles). The extra range will allow the Indian military to establish Agni-V bases in central and southern India, further away from the Chinese border. The Agni-V has been successfully flight tested seven times in total, with three tests occurring in 2018. The most recent launch in December 2018 was described as the final pre-induction flight test (Rout 2018), although several use-trial tests are required before the Agni-V becomes operational (Gupta 2018). Agni-V brings an important new capability to the Indian missile force. Unlike other Indian land-based ballistic missiles, the Agni-V is carried in a sealed canister on the launcher. The first two test-launches used a rail launcher, but since 2015, all launches have been conducted from a road-mobile launcher. The launcher, which is known as the Transport-cum-Tilting vehicle-5 (TCT-5), is a 140-ton, 30-meter, 7-axle trailer pulled by a 3-axle Volvo truck (DRDO Newsletter 2014). The canister design “will reduce the reaction time drastically … just a few minutes from ‘stop-to-launch,’” the former head of India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation said in 2013 (Times of India 2013). Despite widespread speculation in news media articles and on social media that the Agni-V will be equipped with multiple warheads—or even multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs)—there is good reason to doubt that India can or will add MIRVs to its missiles in the near future. There are no official reports that the Indian government has approved a MIRV program, and loading multiple warheads on the Agni-V would reduce its extra range, a key purpose of developing the missile in the first place. The Agni-V is estimated to be capable of delivering a payload of 1.5 tons (the same as the Agni-III and -IV), and India’s first- and second-generation warheads, even modified versions, are thought to be relatively heavy compared with warheads developed by other nuclear-armed states that deploy MIRVs. It took the Soviet Union and the United States hundreds of nuclear tests and 25 years of effort to develop reentry vehicles small enough to equip a ballistic missile with MIRVs. Moreover, deploying missiles with multiple warheads would invite serious questions about the credibility of India’s minimum deterrent doctrine; using MIRVs would reflect a strategy to quickly strike multiple targets and would also run the risk of triggering a warhead race with adversaries. Unless China develops an efficient missile defense system with capability against intermediate-range ballistic missiles, there seems to be no military need for MIRVs on Indian missiles (Kristensen 2013). It seems likely, though, that China’s recent decision to equip some of its ICBMs with MIRVs, and Pakistan’s announcement in January 2017 that it had test-launched a new Ababeel medium-range ballistic missile with MIRVs, will strengthen the hand of those in the Indian military-industrial complex who favor development of a MIRV capability, if for no other reason than to avoid falling behind in MIRV technology. Although Ministry of Defence officials have recently indicated that India’s strategic missile force will be “capped for the present with the Agni-V, with no successor or next series on the horizon or even on the drawing board” (Gupta 2018), India apparently has also begun development of a true ICBM, known as Agni-VI. Official data is scarce, but an article posted on the government’s Press Information Bureau website in December 2016 claimed the Agni-VI “will have a strike-range of 8,000–10,000 kilometers” and will “be capable of being launched from submarines as well as from land” (Ghosh 2016). Whether these claims are accurate remains to be seen; a range improvement of roughly 50 percent to nearly 100 percent of that of the Agni-V seems exaggerated. The US Air Force, National Air and Space Intelligence Center estimates the range is closer to 6,000 kilometers (3,730 miles) (US Air Force, National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2017). India has also converted some of its ballistic missile technology into an anti-satellite interceptor. In March 2019, the Defense Research and Development Organization completed its first successful anti-satellite test (“Mission Shakti”) against one of its own satellites. According to the Indian Ministry of Defence, the interceptor was a three-stage missile with two solid rocket boosters, derived from its indigenous ballistic missile defense program (Ministry of Defence 2019, 96). The destruction of the satellite created a large debris field of hundreds of pieces. And while most reentered Earth’s atmosphere, dozens were kicked into higher orbit by the impact (Grush 2019). Unidentified Indian military sources have also speculated that that the interceptor likely utilizes the propulsion system from the Agni-V ballistic missile, which is still in development (Bedi 2019). Sea-based ballistic missiles India operates a ship-launched, nuclear-capable ballistic missile and is developing two submarine-launched ballistic missiles for eventual deployment on a small fleet of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines. The ship-based ballistic missile is the Dhanush, a 400-kilometer (249-mile) single-stage, liquid-fuel, short-range ballistic missile designed to launch from the back of two specially configured Sukanya-class patrol vessels (Subhadra and Suvarna); each ship can carry two missiles. The Dhanush is a ship-based variant of the Prithvi-II. The most recent test-launch was conducted in February 2018. The utility of the Dhanush as a strategic deterrence weapon is severely limited by its relatively short range; the ships carrying it would have to sail dangerously close to the Pakistani or Chinese coasts to target facilities in those countries, making them vulnerable to counterattack. The two Sukanya-class ships are homeported at the Karwar naval base on the Indian west coast. We suspect the Dhanush will be retired once one or two of the Arihant-class nuclear submarines become fully operational. India’s first indigenous nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN), the INS Arihant, was commissioned in August 2016, but spent most of 2017 and the first half of 2018 undergoing repairs after its propulsion system was crippled by water damage (Peri and Joseph 2018). In November 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that the Arihant had completed its first deterrence patrol, officially marking the completion of India’s nuclear triad. He additionally stated that the deployment constituted “a fitting response to those who indulge in nuclear blackmail” (Singh 2018). The “deterrence patrol” lasted approximately 20 days; however, it is unclear whether the boat was actually equipped with nuclear weapons. Although the Arihant conducted two submerged unit trials of nuclear-capable K-15 missiles in August 2018, sources indicate that the Arihant will primarily serve as a training vessel and technology demonstrator and will not be deployed for nuclear deterrence patrols as additional SSBNs come online (Gady 2018). A second SSBN, the INS Arighat (previously intended to be named Aridhaman), was launched on November 19, 2017, and is expected to be commissioned into the Indian Navy in 2020 (Pubby 2020). The Arighat will be followed by two more SSBNs, temporarily designated S4 and S4* (Bedi 2017), which are scheduled to enter service before 2024 (Pubby 2020).