Master Limited Partnerships, or MLPs have become an increasingly popular equity class, and for good reason. With most MLPs concentrated in the midstream sector (i.e. gathering, storage, and transportation of oil & gas), the business model for many MLPs is built around long-term contracted, fixed-fee, tollbooth style cash flow.

Since most MLPs pay out almost all of their distributable cash flow, or DCF (MLP equivalent of free cash flow and what funds the payout), MLPs generally offer attractive high-yields, which has attracted massive investor attention in this age of historically low interest rates.

Of course, on Wall Street there are always trad-eoffs, and MLPs, like all equities, come with certain risks that investors need to understand before investing their hard earned money.

One of these risks is the complicated nature of how MLPs are taxed, which results in both benefits for investors but also potential headaches. Let's take a look at the most important MLP tax issues to help you determine whether or not MLPs are right for your diversified dividend portfolio.

Unlike a regular dividend stock such as Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), which is structured as a c-Corp, MLPs (which legally must obtain at least 90% of income from natural resources such as oil, gas, timber, or the storage, transportation, or processing of these resources) are structured as pass through entities.

In other words, the partnership exists primarily to "pass through" its cash flow to investors, (who are termed unit holders instead of shareholders) in the form of distributions, a special kind of tax-deferred dividend.

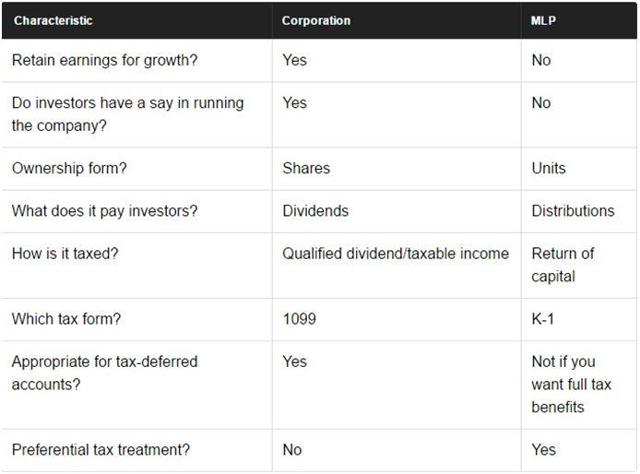

The chart below highlights the major differences between corporations and MLPs.

Source: Motley Fool

In fact, generally an MLP doesn't have any employees of its own. Rather the general partner, which owns a 2% stake in the business, as well as incentive distribution rights and some % of limited units (what retail investors own), provides all management services of an MLP's assets.

In other words, MLPs pretty much exist only to own cash flow producing, natural resource based assets (such as pipelines, and energy storage, and processing terminals), and then pay this out as distributions to the limited partners (i.e. unit holders).

The result is generally a high-yielding income stock, and if chosen correctly, one that offers a highly secure payout, that grows consistently over time, no matter what the underlying commodity is doing.

Thanks to the way MLPs are structured, the MLP itself usually doesn't pay corporate taxes. This helps it avoid the standard double taxation problem that regular c-Corps have, in which the company pays tax on the net income that funds the dividend, and then investors have to pay their own tax on that dividend.

This is because the highly capital intensive nature of the assets it owns means that an MLP's actual earnings are generally much smaller than its distributable cash flow, or DCF. That's because of the high level of depreciation and amortization (i.e. cost of replacing the pipelines and storage tanks) which is deducted from the MLP's operating income, usually on an accelerated depreciation schedule.

In addition, when an MLP acquires assets or another MLP entirely, then it can step up the value of those assets, meaning that it gets to reset the value of those assets to what it paid for them (including the premium paid when acquiring a rival MLP).

This brings me to the major tax benefit of MLPs. When a MLP pays out more distribution per share than it has earnings per share (which is generally the case), the IRS considers this "return of capital," or ROC.

Or to put it another way, the government treats that portion of the distribution as if the company were simply taking the cash that investors gave the MLP (when it sold more shares to raise capital) back to them. Rather than pay taxes on this ROC, this portion of the distribution is simply deducted from the investor's cost basis.

So for example, suppose you bought an MLP at $10 per unit, and it paid out $1.00 in an annual distribution, $0.80 of which is ROC. Then that $0.80 per unit in distribution isn't taxed at all, but rather deducted from your cost basis, which is now $10.00 - $0.80 = $9.20 per unit.

Each time your MLP pays you a distribution, the ROC portion (which is outlined in the annual K-1 form each MLP sends investors at tax time) reduces your cost basis, all the way to zero, at which point the distribution is taxed in its entirety as long-term capital gains.

Only when you sell the units will the government recoup the deferred income represented by the ROC. For example, if you sell the above example MLP for $11/unit a year later, then your long-term capital gain is $11.00 - $9.20 = $1.80. However, long-term capital gains themselves receive preferential treatment.

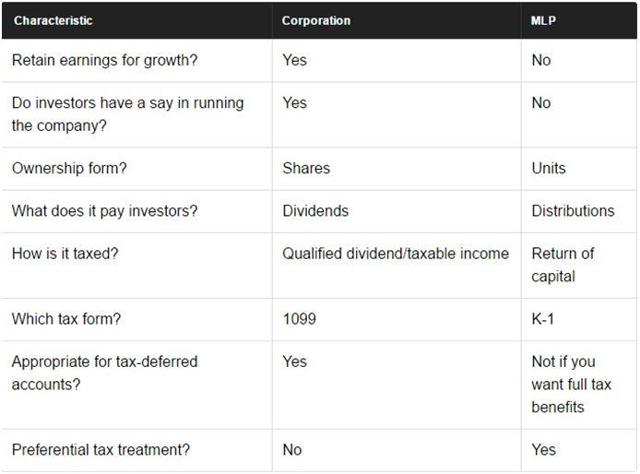

Here is a look at the different taxable income brackets and rates. After identifying which tax bracket you are in, you can figure out what your tax rate is for long-term capital gains.

Specifically, here are the tax rates for long-term capital gains (and qualified dividends) for 2016, which are based on your tax bracket.

In other words, say you are in the 25% tax bracket, and you invest $10,000 in an MLP. Because of the tax deferred benefits of ROC, you can, if you own the units long enough, defer $10,000 in taxable income over time and after that pay just 15%, not 25%, on the distributions once your cost basis hits zero.

Better yet, if you hold the MLP units until you pass on, your heirs can inherit up to $5.45 million per individual, or $10.9 million per married couple tax free. And when they inherit your MLP units (this also applies to shares they inherit) the cost basis resets to the market price on the day you passed on.

Or to put it another way, MLPs can theoretically allow you to defer as much as 100% of your cost basis, permanently, as long as you never sell those units, and tax savings can be passed onto your heirs as well.

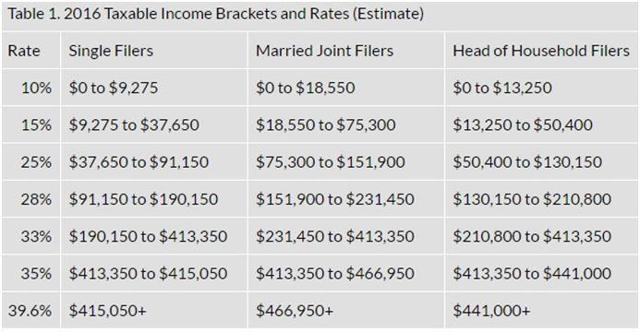

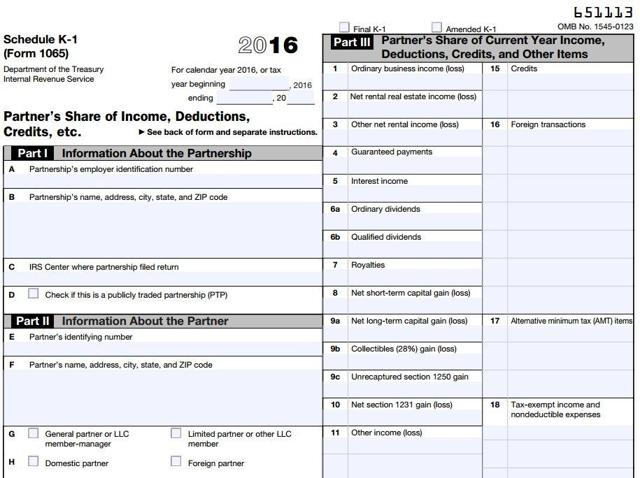

While MLPs certainly have many tax benefits to like, as with most financial things in life there are always tradeoffs. In this case that tradeoff is the K-1 Form 1065 every MLP sends investors around tax time.

This is far more complex than the standard 1099 form that c-Corps issue.

Specifically, let's say your taxable dividend portfolio has a mix of dividend stocks (c-Corps), and Real Estate Investment Trusts, or REITs. At tax time you can pull up a consolidated 1099 from your broker that will list all the consolidated dividends, both unqualified (from REITs, BDCs, and yieldCos), which are taxed at your top marginal tax rate, and qualified (c-Corp) dividends which are taxed as long-term capital gains, meaning 0%, 15%, or 20%.

But because an MLP's distributions consist of income, ROC, and something called Unrelated Business Taxable Income, or UBTI, each K-1 will be different, and can vary from year to year.

In other words, the downside of owning an MLP such as Enterprise Products Partners (EPD), with its generous distribution, is higher complexity at tax time, especially if you happen to own several MLPs. That's because each K-1 will tell you how much to adjust your cost basis for that year.

Now, understand that I'm not trying to dissuade anyone with owning quality MLPs such as Magellan Midstream Partners (MMP) or Holly Energy Partners (HEP). After all most tax preparation software programs, such as TurboTax, can easily handle K-1s, and many MLPs (including Enterprise Products Partners) allow you to enroll in online K-1 programs that offer personalized tax schedules.

Just be aware that owning MLPs means a higher tax complexity (cost of doing business in this high-yield world), especially when it comes to owning MLPs in tax advantaged accounts such as IRAs or 401Ks.

Many people look at the added tax complexity of MLPs and might think, "a tax advantaged account can help me avoid this mess." While this is technically true, as the account custodian will aggregate and summarize all the MLP tax info in a 990-T form, there are two things to keep in mind before you purchase MLPs for your IRA or 401K.

First, you are losing a lot of the tax benefit because these accounts are already tax deferred (Roth IRAs especially). So you are not gaining the full advantage of the tax benefits by owning MLPs in such accounts.

This is especially true once you hit 70.5 years of age and have to start making minimum required distributions. That's because whenever you sell MLPs in a tax advantaged account you will be taxed at your top marginal tax rate, not the lower, long-term capital gains rate. In addition, there's the issue of UBTI for those with larger enough MLP holdings.

Unrelated Business Taxable Income is basically any "gross income derived by any organization from any unrelated trade or business regularly carried on by it." It exists to help ensure that MLPs don't gain an unfair advantage over regular corporations due to things such as unrelated debt financed income, or UDFI (a subtype of UBTI).

Think of it like this. If I were to use my Roth IRA, which is permanently tax exempt, to open a business, such as a restaurant or gas station, then I could use my tax exempt status as a weapon against my competitors, undercutting them on price, stealing market share, and potentially driving them out of business.

This is why Congress created UBTI in 1950, to ensure that tax exempt organizations could still operate under their original charters but wouldn't be able to gain an unfair advantage in the market place.

The IRS gives every taxpayer a $1,000 UBTI annual allowance. As long as your total portfolio of MLP holdings (across every account you own) doesn't produce more than this amount, you don't have to report it or pay taxes on it. Now keep in mind that many MLPs actually produce negative UBTI which cancels out the positive UBTI from other MLPs.

So the actual chance that your account would breach this $1,000 UBTI limit is small, unless your IRA is heavily concentrated in just a few MLPs that happen to generate a substantial amount of UBTI in a given year. If your accounts (total, including taxable accounts) produce over $1,000 in UBTI then you must report it, and pay taxes on it, even if the units are held in a tax sheltered account.

That added headache, in addition to the lost tax advantages is why it's best to own MLPs in taxable accounts only.

Despite the tax headaches that can come from owning a broadly diversified portfolio of MLPs, as long as you keep in mind the need to do your research, be highly selective, and only invest in the best managed names in the industry, some MLPs can be a reasonably attractive high-yield addition to for a well-diversified dividend portfolio.

Just don't forget that when it comes to tax advantaged accounts you probably want to stick to REITs, BDCs, and yieldCos (all of which don't generate UBTI and lack the deferred tax benefits of MLPs), while holding MLPs only in taxable accounts. Consulting with a tax professional isn't a bad idea for MLP investors given the number of tax issues to consider.